Having Fun with Microsoft IoC Container for .NET Core

The objective of this post is to configure and use Microsoft’s default dependency injection container from scratch to understand how it all hangs together when in action. There are many other great articles explaining Dependency Injection and Inversion of Control (DI & IoC from now on) in ASP.NET Core out there. This article assumes that you understand those principles. So I will not be covering those.

We will start with a simple console application, configure an IoC container, and have some fun with it by diving into the .NET Core DI Extensions’ source code.

💡 Follow along with the code from my repository

Microsoft’s IoC Container in .NET Core

The .NET Core IoC container is located in Microsoft.Extensions.DependencyInjection namespace. Let’s look at what are the steps involved in order to use this in our application.

- We need to add this assembly via NuGet.

- Types must be registered with

ServiceCollection - Types are retrieved from

ServiceProvider

We will start off with a simple console application and see how we can achieve the above steps.

Setup

Let’s start by creating a console application.

dotnet new console -n IoCTutorial

dotnet new sln

dotnet sln add IoCTutorialOpen it up in your favourite IDE and you are ready to follow along. I won’t be using any other dependency (such as logging) just to keep this tutorial simple.

Let’s go ahead and add the DI assembly from NuGet.

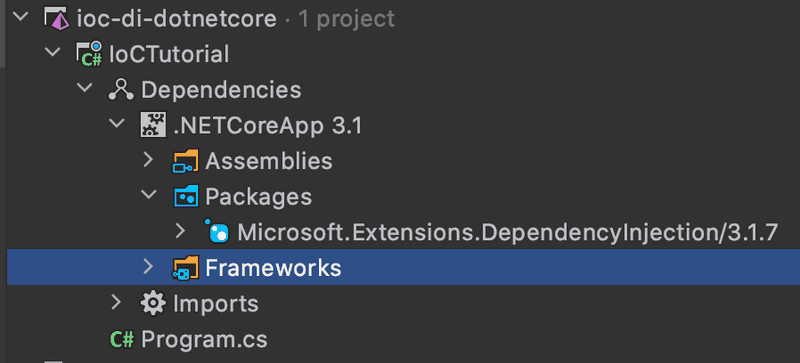

dotnet add package Microsoft.Extensions.DependencyInjectionYour project structure should now look like this.

Let’s add two classes into our project; MyService and MyDependency. Here’s what’s gonna go into those two classes.

MyService.cs

public class MyService

{

private readonly MyDependency _myDependency;

public MyService(MyDependency myDependency)

{

Console.WriteLine("Constructed MyService");

_myDependency = myDependency;

}

public void DoSomething()

{

_myDependency.DoWork();

}

}MyDependency.cs

public class MyDependency

{

public MyDependency()

{

Console.WriteLine("Constructed MyDependency");

}

public void DoWork()

{

Console.WriteLine("Doing some work in MyDependency");

}

}As we can see, MyService has an (aptly named 😅 ) dependency on MyDependency. In order to invoke our service, we need to pass an instance of the required dependency into its constructor. In our driver code (Program.cs) without any IoC stuff, we could do something like this.

var myService = new MyService(new MyDependency());

myService.DoSomething();This is baaaaad 💀. Problem with this is, now we are responsible for managing the dependencies, their lifetimes (and also violates SOLID principles) etc. Let’s fix this by using the IoC container. We will simply give them a scoped lifetime.

// Register our types in the container

var container = new ServiceCollection();

container.AddScoped<MyDependency>();

container.AddScoped<MyService>();

// Build the IoC and get a provider

var provider = container.BuildServiceProvider();If you aren’t familiar with service lifetimes, it’s best if you refer to the official documentation before continuing on.

💡 Note that you don’t have to instantiate ServiceCollection in an ASP.NET Core Web or Worker Service application. You would ideally register your services using the IServiceCollection in the Startup class.

The quick & dirty service registration

Once we have set this up, we need to call BuildServiceProvider method on the container. This returns us a ServiceProvider as a result. Remember that we first need to register our types in the container (ServiceCollection) and then retrieve them using the provider. Bear with me on this one as we are using the concrete implementations rather than interfaces for this initial cut.

// Get our service and call DoSomething()

var myService = provider.GetService<MyService>();

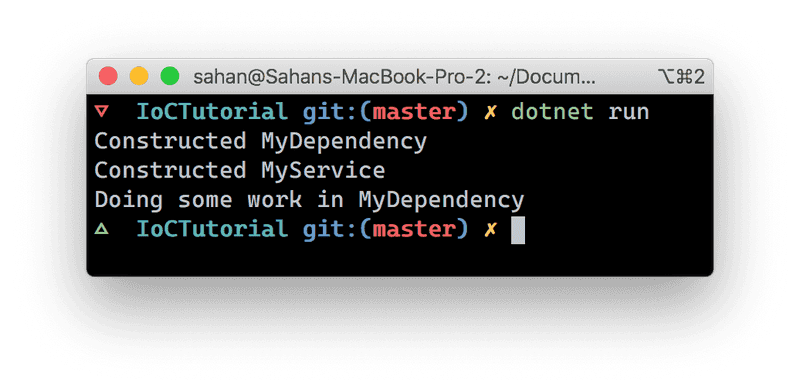

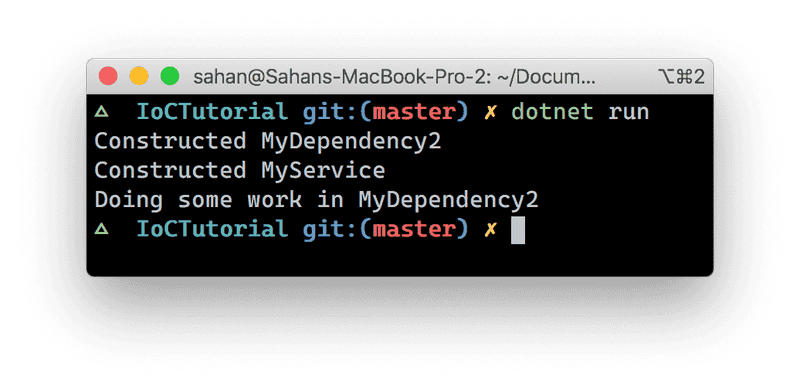

myService.DoSomething();Now when we run this, it should create an instance of MyDependency, construct an instance of MyService and run the DoSomething() method.

Notice how we never constructed MyDependency because the DI framework resolved it and did the constructor injection for us. Nice!

Internals of ServiceCollection and ServiceProvider

Looking at our code, the ServiceCollection holds a bunch of ServiceDescriptors and provides some utility methods to manipulate it. ServiceDescriptors are really the objects that describe (type, implementation, lifetime etc.) our service registrations.

public class ServiceCollection : IServiceCollection

{

private readonly List<ServiceDescriptor> _descriptors = new List<ServiceDescriptor>();

public int Count => _descriptors.Count;

public bool IsReadOnly => false;

public ServiceDescriptor this[int index]

{

get

{

return _descriptors[index];

}

set

{

_descriptors[index] = value;

}

}

public void Clear() {...}

public bool Contains(ServiceDescriptor item) {...}

public bool Remove(ServiceDescriptor item) {...}

void ICollection<ServiceDescriptor>.Add(ServiceDescriptor item) {..}

// Other methods removed for brevity

}In the subsequent sections, we will look at how it gets utilised.

The AddScoped (and other service registration extension methods) method just adds our service registration (as a ServiceDescriptor) into the above _descriptors list.

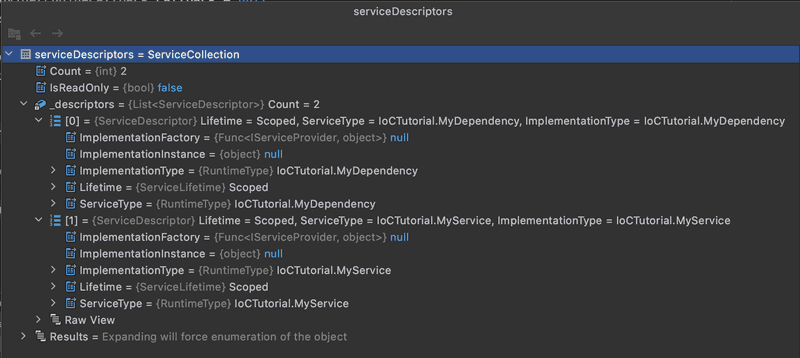

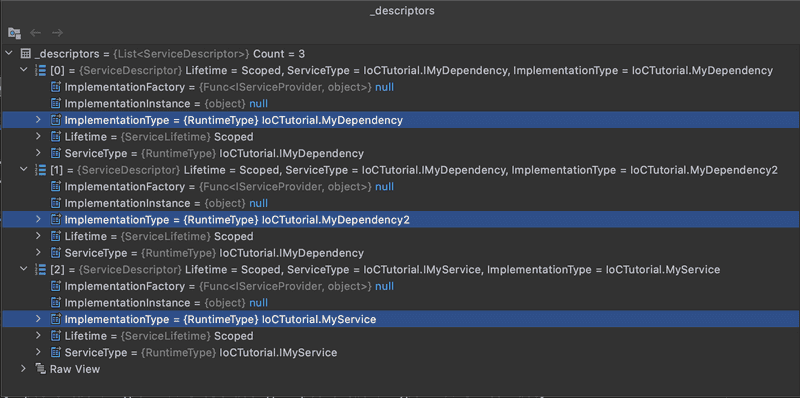

Looking at the internals of the BuildServiceProvider extension method, we can see that it actually instantiates a new service provider with our given service registrations. As we saw earlier these service registrations are passed in as a ServiceCollection and if you put debug this, you will be able to see the following:

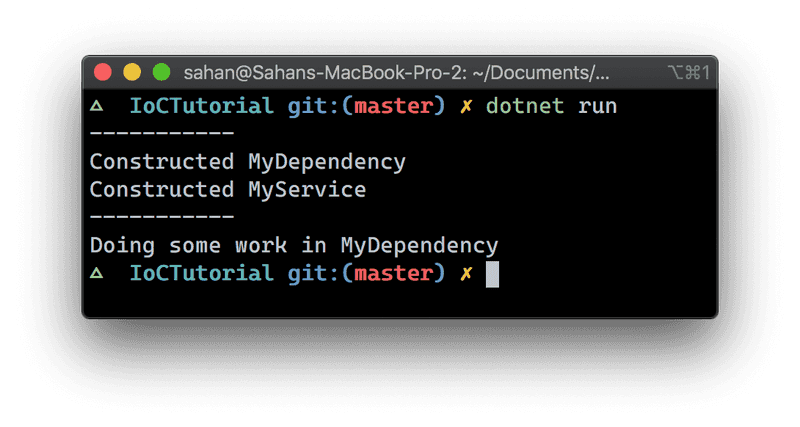

If you are interested, one observation I made was to get an idea of when it actually instantiates our types. In our Program.cs if you update it as below,

var provider = container.BuildServiceProvider();

Console.WriteLine("-----------");

var myService = provider.GetService<MyService>();

Console.WriteLine("-----------");

myService.DoSomething();Should give you,

See the dotted line before “Doing some work in MyDependency”? I initially thought that these types would have been constructed when we built the service provider. However, it seems that they are instantiated when we call provider.GetService<MyService>(); instead. This should, however, not to be confused with service lifetimes in an ASP.NET Core web application where service lifetimes play a major role in the request pipeline.

💡 The IoC container will instantiate our implementation types when the GetService

() method is called, not when the IoC container is built.

Looking at the implementation of the ServiceProviderEngine’s code you will see that the data structure that holds all our type registrations is really a ConcurrentDictionary. If you drill down in the call chain of GetService far enough, you would come across the following class in the source of DI extensions.

So, we have an idea of how we can register services in the IoC container. Nevertheless, this can still be improved by mapping interfaces rather than using concrete classes. We will look at it in the next section.

Replacing Concrete Classes with Interfaces

Let’s extract interfaces for MyService and MyDependency

public interface IMyService

{

void DoSomething();

}public interface IMyDependency

{

void DoWork();

}Nothing interesting here. Let’s just implement these two interfaces in their corresponding classes.

Our MyService will now use the interface instead of the concrete class.

public class MyService : IMyService

{

private readonly IMyDependency _myDependency;

public MyService(IMyDependency myDependency)

{

Console.WriteLine("Constructed MyService");

_myDependency = myDependency;

}

public void DoSomething()

{

_myDependency.DoWork();

}

}In our Program.cs, we will update the following lines to use the abstractions instead of concrete classes,

container.AddScoped<IMyDependency, MyDependency>();

container.AddScoped<IMyService, MyService>();Now when we run the application, we will get the same result. However, to make things interesting, let’s add another MyDependency class that implements IMyDependency interface. Without spending too much time on a name, let’s name that MyDependency2 and register it in the IoC container.

container.AddScoped<IMyDependency, MyDependency>();

container.AddScoped<IMyDependency, MyDependency2>(); // New implementation

container.AddScoped<IMyService, MyService>();What do we get now?

It’s no longer using MyDependency, but using MyDependency2 instead.

💡 Remember, if you add multiple concrete implementations for the same interface, it will always pick up the last one that got registered, by default.

Unravelling why we get the last registered implementation type

So, how do we register multiple implementations for the same service type? It’s not supported as you might already know or have come across this discussion on Github. Looking at the internals of the GetService() method we can uncover why this happens.

If you debug the ServiceCollection, you will be able to see that our two implementation types for IMyDependency are still there.

So there has to be something in the call stack which hands over the last registered implementation type to the service provider. If you start off from GetService() method in ServiceProviderServiceExtensions class, you would end up in ServiceProviderEngine’s GetService() method’s implementation.

internal object GetService(Type serviceType, ServiceProviderEngineScope serviceProviderEngineScope)

{

if (_disposed)

{

ThrowHelper.ThrowObjectDisposedException();

}

var realizedService = RealizedServices.GetOrAdd(serviceType, _createServiceAccessor);

_callback?.OnResolve(serviceType, serviceProviderEngineScope);

DependencyInjectionEventSource.Log.ServiceResolved(serviceType);

return realizedService.Invoke(serviceProviderEngineScope);

}RealizedServices is a ConcurrentDictionary that keeps track of our service types and a Func to retrieve the implementation type by visiting the corresponding call sites in the dependency tree. The _createServiceAccessor actually refers to CreateServiceAccessor which does the above.

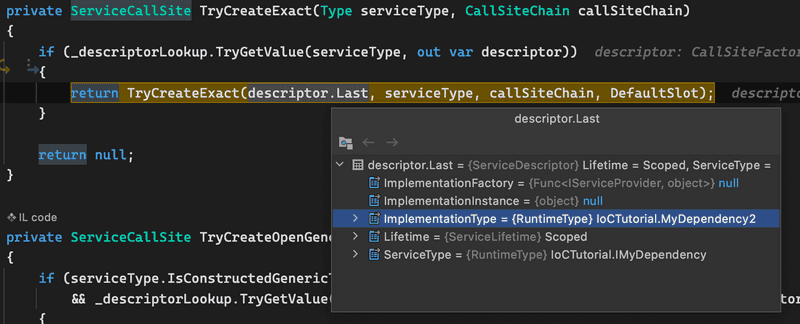

To find the “why” of this, we need to dig into GetCallSite method. This will hopefully navigate you through to CreateCallSite method in CallSiteFactory.cs class. If you find the following lines, that could give you a hint where to look at next. In our case, it will call the TryCreateExact method because it’s neither an Open Generic nor an Enumerable.

...

var callSite = TryCreateExact(serviceType, callSiteChain) ??

TryCreateOpenGeneric(serviceType, callSiteChain) ??

TryCreateEnumerable(serviceType, callSiteChain);

...Taking a peek inside TryCreateExact you will be able to see the following like which passes in the last implementation type of the service type we are looking for. There you have the answer for what we were searching for from a more granular level of detail.

A way to access multiple implementations of same service type

Let’s say in the rare situation where you would want to invoke both dependencies somewhere in your code; how would you achieve that?

I have changed the MyService class a little bit to give you an idea of how you can sort of do that. The key here is, we need to inject our dependencies as an IEnumerable which will give us access to the service registrations of a given type.

public class MyService : IMyService

{

private readonly IEnumerable<IMyDependency> _myDependencies;

public MyService(IEnumerable<IMyDependency> myDependencies)

{

Console.WriteLine("Constructed MyService");

_myDependencies = myDependencies;

}

public void DoSomething()

{

foreach (var dependency in _myDependencies)

{

dependency.DoWork();

}

}

}Or better yet, you can specifically select the dependency you want with a little bit of LINQ by doing something like:

_myDependencies.FirstOrDefault(x => x.GetType() == typeof(MyDependency))?.DoWork();💡 Note that the IoC container will only resolve and inject the collection of services when the parameter type is an

IEnumerableand not any other type such as IList, Array etc. Otherwise, you can expect anInvalidOperationException.

Not the world’s best solution, but gets the job done 🙂 Another downside to this is having to manually register the services rather than making use of assembly scanning. You can also play around with TryAddEnumerable extension method to see how you can improve this implementation depending on your use case.

A quick detour: how does it resolve an IEnumerable?

Taking a quick detour, let’s see how we got both our MyDependency and MyDependency2 when we injected an IEnumerable.

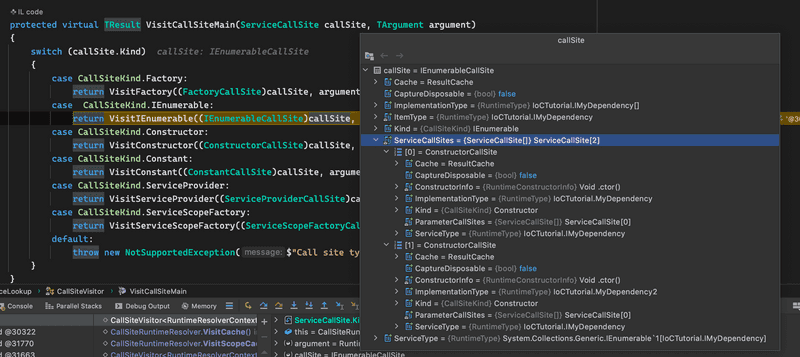

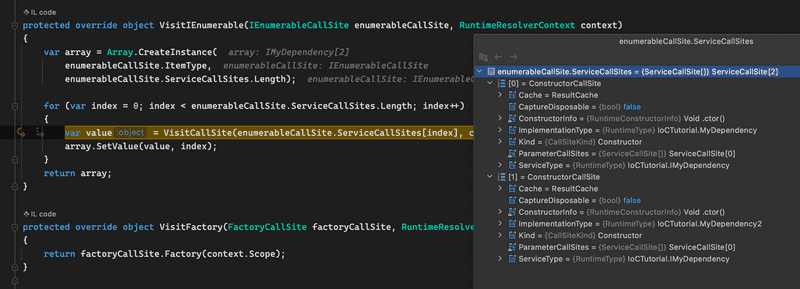

When it does the service lookup, depending on the lifetime of the service, it will access different caches of the service provider engine. This happens in the VisitCallSite in CallSiteVisitor class. During this detour, you will also encounter some impressive locking code with Monitor 👀. Once you run through some more hoops you will end up in VisitCallSiteMain method which will call the VisitIEnumerable method.

If you carefully look at the ServiceCallSites in the above screenshot (highlighted in blue) you can see it has references to our MyDependency and MyDependency2 types under ImplementationType params in their corresponding sections. Since we requested an IEnumerable it knows that it needs to resolve all the dependencies we have registered under IMyDependency type.

Now, if you have a look VisitIEnumerable method you would see that it visits each implementation type’s constructor in a for-loop.

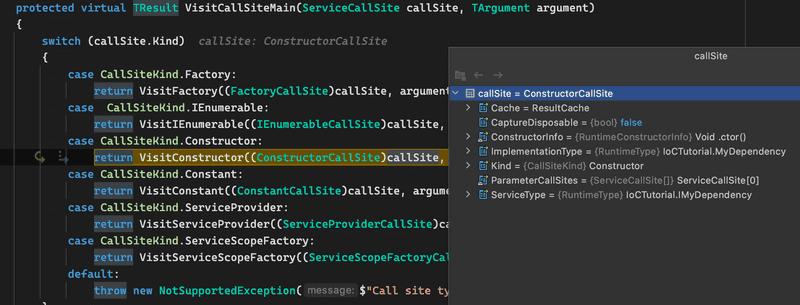

Now that we are iterating through each of the implementation types we will again go through the VisitCallSite method (doing the service lookup in the cache etc.) call chain as before and end up in the VisitCallSiteMain method.

Déjà vu? yet again we are visiting the VisitCallSiteMain method as before because now we are resolving each dependency of type IMyDependency by visiting the ctors in the above loop. In the VisitConstructor method, by using reflection (ConstructorInfo.Invoke() method) it will call the constructor on our implemented type and return it. Note that this will happen only during the initial call to the lookup the service and subsequent calls depends on the lifetime (by using the internal cache).

As we can see, Microsoft’s default IoC container has all the essential capabilities but also lacks some advanced features like assembly scanning, service decorators that you would get in frameworks like Autofac, Scrutor etc.

Summary

To summarise, we first looked at how we can easily bring in Microsoft’s IoC container into a console application. Then we had a look at service registration and retrieving the services using a provider. Finally, we had some fun with it by using multiple implementations of a given service type and some of the learnings along the way. This is just the tip of the iceberg though. There’s more stuff to dive into, which I am hoping to cover in the future.

Hope you enjoyed this post and see you next time. Cheers! 👋